Free shipping

Stai acquistando da

ITALIA

Brands

Other services

Stores

Brands

Other services

Book technical assistance @@@button@@@

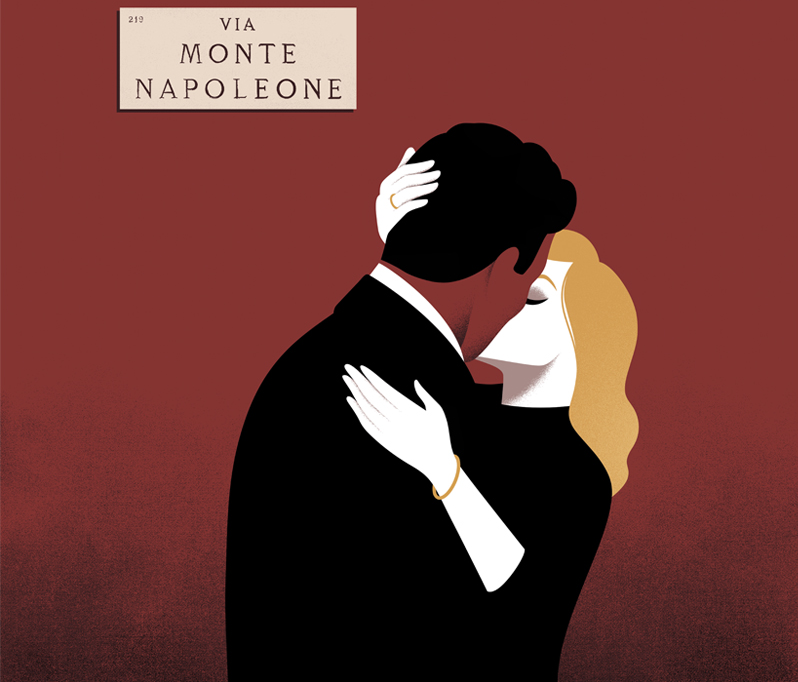

Flagship Store

Rolex Boutique

Patek Philippe Boutique

Vacheron Constantin Boutique

A. Lange & Shöne Boutique

Hublot Boutique @@@bottom_bar@@@

Store locator

Book an appointment @@@button@@@